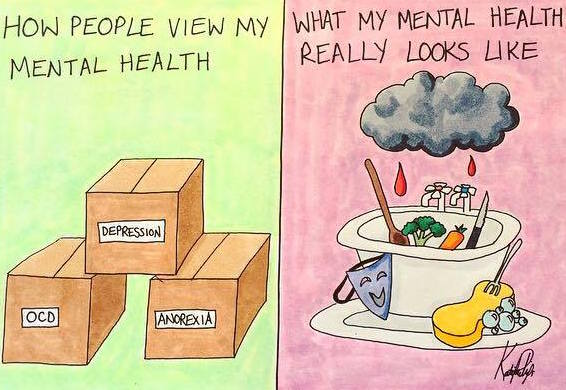

Whenever a doctor or health care professional looks at my notes for a brief overview of my mental health, they will see three separate words:

Depression

OCD

Anorexia

The words may not be on separate lines as I have illustrated above, but there is always some kind of gap between them, even if that gap is only in the form of a comma or perhaps a space bar. As a brief summary of my mental health, I suppose those three words can give you a reasonable idea of my struggles. Nevertheless, the idea gathered from those three words is only a reasonable idea, as my illnesses are far more intertwined than many people realise. If I were to write the three diagnoses in a more accurate form, they would look like this:

Now granted, that wouldn’t be as easy to decipher as the former example (although doctors are used to examining messy handwriting…), but it would be a lot closer to the truth and what mental illnesses feel like.

I think that some professionals, even those working in mental health, have a a problematic view of the illnesses that they treat by thinking that they can be separated into neat tidy boxes as easily as I can separate these words just by hitting the space bar. Don’t get me wrong, I would LOVE it if they were right and that mental illnesses really did come in boxes, much as the title of this blog post suggests. For one thing, if mental illnesses came wrapped and caged within physical cubed objects it might be possible to operate on a person and physically remove the cause of any problems with the ease with which they remove a tonsil (or tonsils…I think people have more than one tonsil…I really need to get round to counting mine one of these days. It has been on my to-do list for years). More importantly though, were mental illnesses to be so easily distinguished from each other, it would make treatment far more straight forward.

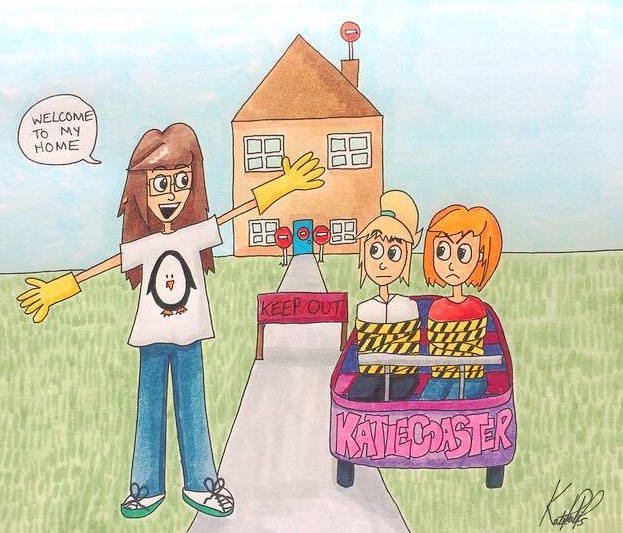

In terms of treatment I get for my mental health, I have several very separate teams of people in several very separate buildings. There is the hospital for my eating disorder which always smells of cauliflower cheese, there is the general mental health centre for my depression (which doesn’t smell much of cauliflower or cheese), and if I get accepted to the new service I was assessed for two weeks ago, I will have another building to attend appointments in regarding OCD (I haven’t been in that building yet so I am afraid I cannot document how much this place smells of either cauliflower or cheese but I will be sure to inform you the moment I know).

When I walk into each building every week, I am expected to talk about and deal with the illness that has been designated to that service. It’s as if they think I can leave my other mental illnesses by the door still packaged in their neat little boxes, without realising that the three are inextricably linked in a complex mesh even I cannot understand, so if one comes into the room with me, the other two cannot help but tag along.

For example, because of my mental health problems I have a lot of behaviours. One of these is that I tie my hair up repeatedly before a meal in a routine that can take as short as five minutes or as long as several hours. Now, if asked, I would say that this behaviour is an eating disorder behaviour as I only carry it out prior to a meal. If I wasn’t about to eat something, I could tie my hair up in seconds so I would say that as the anxiety is more about preparing for the impending meal, the hair tying is a part of anorexia. That said, there are many professionals who have argued with me that it is in fact an OCD behaviour, an obsessive ritual of repetitive compulsions that make no sense in rational terms. Who is to say which one of us is right in our conclusion? Both have fair points and it is easy to argue either way. What about the fact that I cut the majority of foods into four separate pieces? It is related to food so it could be my eating disorder, yet the numbers and rigidity with which I handle a knife is far more akin to the OCD. So what is the answer? Who is the culprit in causing each of these rituals? Who can solve this mystery? Someone find Poirot immediately! (Finding Miss Marple or Sherlock would also be helpful but they are second choices because they don’t have fancy moustaches.)

It isn’t that I particularly care which of my diagnoses is causing the problem, I just want them to go away, yet without knowing the specific name of the villain in this situation it is hard to find a professional able to help me. When I talk to the eating disorder services they tell me to talk about the ritualistic eating behaviours with the OCD team yet the OCD team tell me that is a job for the eating disorder hospital and as a result, treatment for these behaviours tends to slip through the cracks without ever getting a chance to materialise because they don’t fit into the neat boxes everybody wants them to. In this example it isn’t really that big of an issue as in spite of not fitting into the neat boxes all the time, I still receive treatment for both OCD and anorexia even if is is unable to solve the issues where behaviours are a combination of the two. The biggest issue however, is when this lack of mental health diagnoses tidiness doesn’t just get in the way of someone’s treatment, but gets in the way of them being accepted for treatment at all.

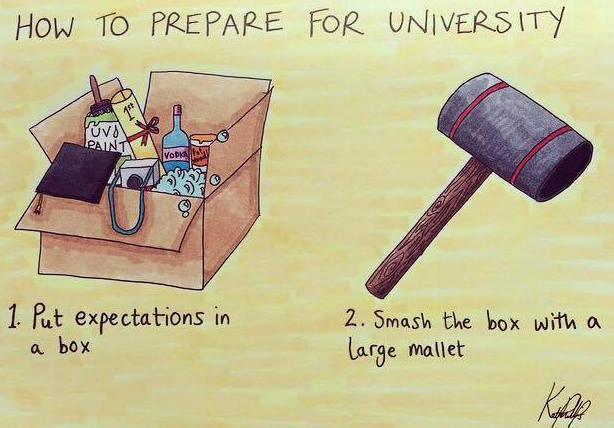

All over the world people including myself who are seriously struggling with mental health problems are referred to services that turn them down not because treatment is not needed, but because the case doesn’t exactly fit into a specific list of criteria. So why not broaden the criteria? Obviously I realise that the issue causing all of these problems is a lack of funding for mental health services and thus the need to have specific criteria to narrow the case load down (don’t worry, when I become prime minister I am going to be chucking so much funding at mental health services that this problem will be solved. I am also going to chuck in a lot of funding to investigating the invention of a mug that keeps a cup of tea at exactly the right temperature for hours on end, but that is a story for another time).

Still, issues with funding or not, it makes absolutely no sense to me seeing the complex soup that is mental health being separated into neat little blocks. I myself have been turned away from services for being “too complex”, which is basically like saying “yes you are crazy and in need of help but you do not fit into our definition of crazy so we are going to have to send you elsewhere only to be told the same thing and referred somewhere new all over again”.

Labelling a mental health problem with a diagnosis like “OCD” or “anorexia” is of course incredibly useful in terms of narrowing down a problem, but even then every person with OCD will experience the illness differently and that needs to be taken into account with the way they are treated as each experience is equally valid. If you go to the supermarket there will be a whole aisle of baked beans, tin upon tin all labelled “baked beans” and sure, they are all “baked beans”, but each one is slightly different just as each person with a diagnosis is slightly different. Nobody should be refused treatment for being the “wrong kind” of crazy, the fact that there is any kind of crazy should be enough.

That is why I wish mental health problems came in boxes, but alas I fear that is one wish that won’t ever come true (much like the wish I made on my 4th birthday to become a penguin. It has been 20 years and I am still waiting. Haven’t even got a sign of a flipper yet.) However, if it is a wish that won’t come true then we need to change the way we see mental disorders and indeed treat them rather than acting as if things are far simpler than they are in reality. It is time we realised that mental illnesses don’t come in boxes and the people who suffer from them don’t either. Rather than refusing to help those of us with a bit of a confusing mess going on, we need to roll our sleeves up and dive in anyway. Everyone is different, yet all are equally worthy of support.

Take care peeps.